Share This Article

How a Brief Dustup With the World Shaped the Identity of a Town

Sudbury’s history is filled with the “stranger comes to town” kind of stories. What’s most remarkable is that Sudbury exists as it is today, in part, because of fierce resistance to “outsiders” over the years.

Most residents are familiar with the story of Henry Ford and his ownership of the Wayside Inn. Others know that Ford tried to turn Sudbury into a factory town, but his plans were foiled by a single landowner, Giuseppi Cavicchio.

Another remarkable story from that era, the story of the United Nations in Sudbury, flies under the radar.

Curtis Garfield’s “Sudbury, 1890-1989: 100 Years in the Life of a Town” chronicles this chapter of Sudbury history in detail. While some local historians question the sourcing in that book, many of the key details are consistent with another book “Capital of the World: The Race to Host the United Nations” which was written by Charlene Mires.

The story goes something like this: Some strangers came to town, the locals have some concerns, and an international incident ensues.

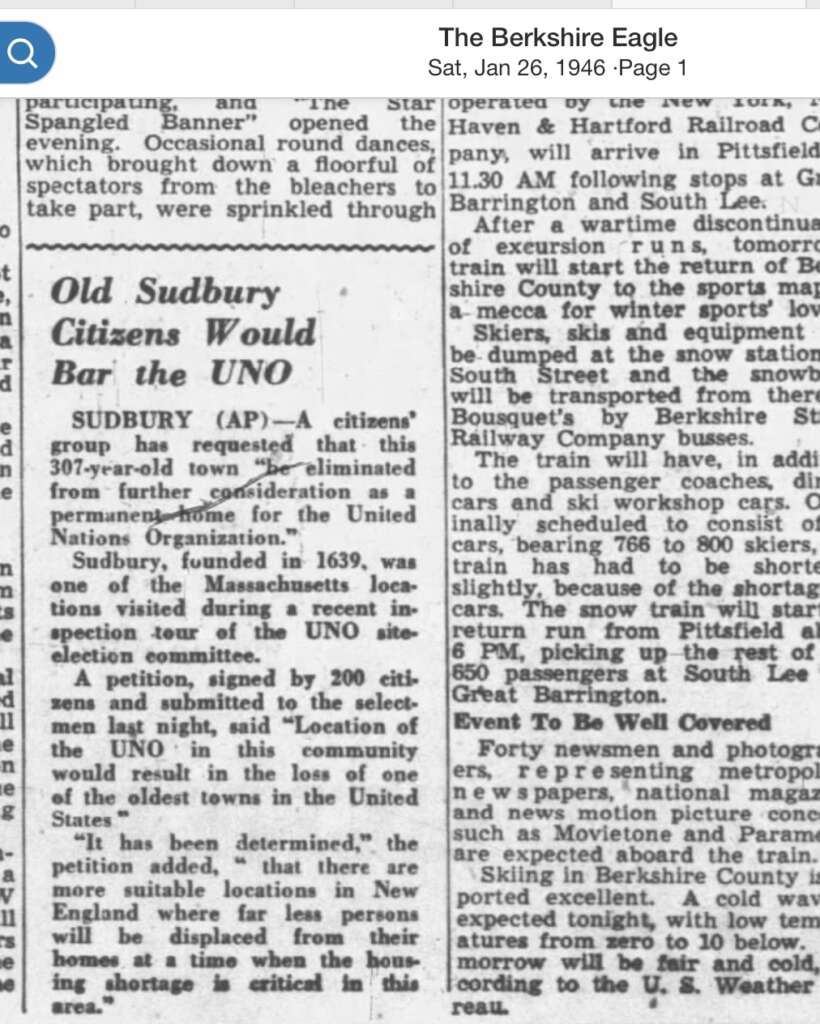

A site selection committee made a 1946 trip to Sudbury, which included a journey to the fire tower at the top of Nobscot Mountain. Garfield quotes Stoyal Gavrilovic of Yugoslavia (a member of the site selection committee) saying “We may be looking at the spot where man finally will achieve enduring peace and where all injustices to men will be corrected without conflict.”

The appeal of this area of Massachusetts was multi-faceted, as recounted in the chapter. But there was one piece of criteria that likely triggered the local response: because this area was sparsely populated, the proposed 50 square-mile United Nations headquarters would displace less residents than other, more densely populated sites.

Hundreds of residents signed a letter imploring the Select Board to tell the United Nations they were not welcome. Other residents began a letter writing campaign, which soon spread to surrounding towns. Suffice it to say, the letters were not too kind. But Garfield credits the Knights of Columbus with taking all of Massachusetts out of contention. They opted to insult Russia, calling them “Godless Russia,” which irked the Russians enough to shift some key votes to New York… which had identified a site and some Rockefeller funding to sweeten the pot.

As it turns out, Sudbury’s residents weren’t exactly being “NIMBY” (“not in my backyard) about the project. In fact, their fear of losing their property was grounded in the fact that the federal government had taken their property some years earlier for a munitions dump.

Today’s residents know that land as the Assabet River National Wildlife Refuge. That’s a story for another day, but the book “The Ammo Dump” is a great read for those interested.

Property Rights or Identity Crisis?

One of the points that Mires makes in “Captial of the World: The Race to Host the United Nations” is that Sudbury and other towns weren’t contacted by State of Federal authorities about the potential location of the United Nations. Mires suggests the land taking that happened during the war was an unhealed wound. “Why hadn’t they been consulted by either the UN or the governor? The community already had lost three thousand acres to the federal government for a munitions dump during the war, and that seemed like sacrifice enough.”

On some level, it was a classic battle over property rights. But the literature suggests that much more was at play.

Nearby Concord, including Walden Pond, were also under consideration. It’s hard to imagine an identity for Sudbury without the Wayside Inn, or even just the few remaining remnants of it’s agricultural history. Imagine if Walden Pond was fenced off to the public, subsumed into a massive United Nations campus?

Some residents perceived an international threat that would seek to displace them, all at a time when homeownership was skyrocketing and embedding itself into the notion of the American dream. Mires wrote “As in Concord and Sudbury, Massachusetts, the protest reflected a tension for localities in the postwar world, where deep attachments to home coexisted with inescapable connections to international affairs.”

Back To The Future

80 years after the United Nations Site Selection Committee toured Sudbury, the Town has had many more battles over property rights and the character of the Town. The Eversource transmission line beneath the Mass Central Rail Trail is just one recent example where the Town and its people fought for years to prevent the infrastructure project from moving forward. In that case, the town did not succeed, but in other cases it did. The 2021 Sudbury Station land swap saved the iconic character of Sudbury’s historic Town Center, for example.

With no access to major highways, and a town that is largely built out to the max, it’s hard to imagine a stranger coming to town to gobble up Sudbury’s land these days. And it’s safe to assume the trustees of the Wayside Inn aren’t going to sell the land and historic buildings to Elon Musk. But small skirmishes remain — including recent concerns raised by the Park and Recreation Commission about the aesthetics of a proposed solar canopy in the Haskell Field parking lot, proving that the more things change, the more things seem to stay the same in Sudbury.

It’s uncanny that four decades have passed since the United Nations dustup and the residents of Sudbury are still protesting government overreach, all while the role and effectiveness of the United Nations is thrown into question by the federal government and growing geopolitical conflicts.

In fact, the local-global link in little, old Sudbury seems to be flourishing, while the connection to the United Nations appears to have worked its way into the local identity. Lincoln-Sudbury Regional High School offers a “portrait of a graduate” that calls for students to be global citizens… It goes on to define that as someone who “Works to forward the United Nations Sustainable Development goals.”

Yes, Sudbury has preserved much of its identity through land acquisitions, historic preservation, targeted bylaws, and institutions like Lincoln-Sudbury. But with all the chatter about a “changing world order” at Davos, an unrelenting housing and affordability crisis locally, and the ever-present beating drum of change, it seems inevitable that Sudbury’s identity will be challenged once again.